EXCLUSIVE: AG Bird's Silence on 27A Database Revealed Amidst Sheriff Pursuit

As AG Bird Uses Iowa Code 27A to Target a Local Sheriff, Her Office Evades Scrutiny on Its Own Compliance with the Law's Transparency Rules.

I. Introduction: Legal and Political Intrigue in Rural Iowa

Legal and political intrigue continues to escalate in rural Iowa. In Winneshiek County, Sheriff Dan Marx now finds himself at the center of investigation by the state's highest legal office, targeted under a controversial and largely "untested" state law, Iowa Code Chapter 27A. The catalyst? Sheriff Marx's exercise of free speech—his outspokenness on social media regarding sensitive issues like immigration, local control, and what he perceived as authoritarian overreach. His views quickly drew the ire of influential conservative lawmaker Steven Holt, who is said to have carried the matter directly to Governor Kim Reynolds.

Now, Attorney General Brenna Bird, a close political ally of the Governor and an expected contender for the 2026 gubernatorial race—has taken up the case against Marx.

This isn't just a local dispute; it's a chilling example of how state power can be mobilized, potentially for political retribution, using laws that have languished untested, their full implications unknown even to those sworn to uphold them. As previously explored in the Untested Waters series, Iowa Code 27A contains provisions, particularly sections 27A.3 and 27A.9, concerning the potential for misuse, and it seems that potential is now being realized with increasing clarity. The story takes a more disturbing turn, one that cuts to the heart of transparency and accountability: the Attorney General's office is actively wielding Chapter 27A to pursue legal action against a publicly elected Sheriff while seemingly failing to comply with its own clear obligations under the law's transparency rules.

II. Iowa Code Chapter 27A: The "Sanctuary Cities" Law and its Mandates

A. Defining Key Terms: “Local Entity” and “Detainer Request”

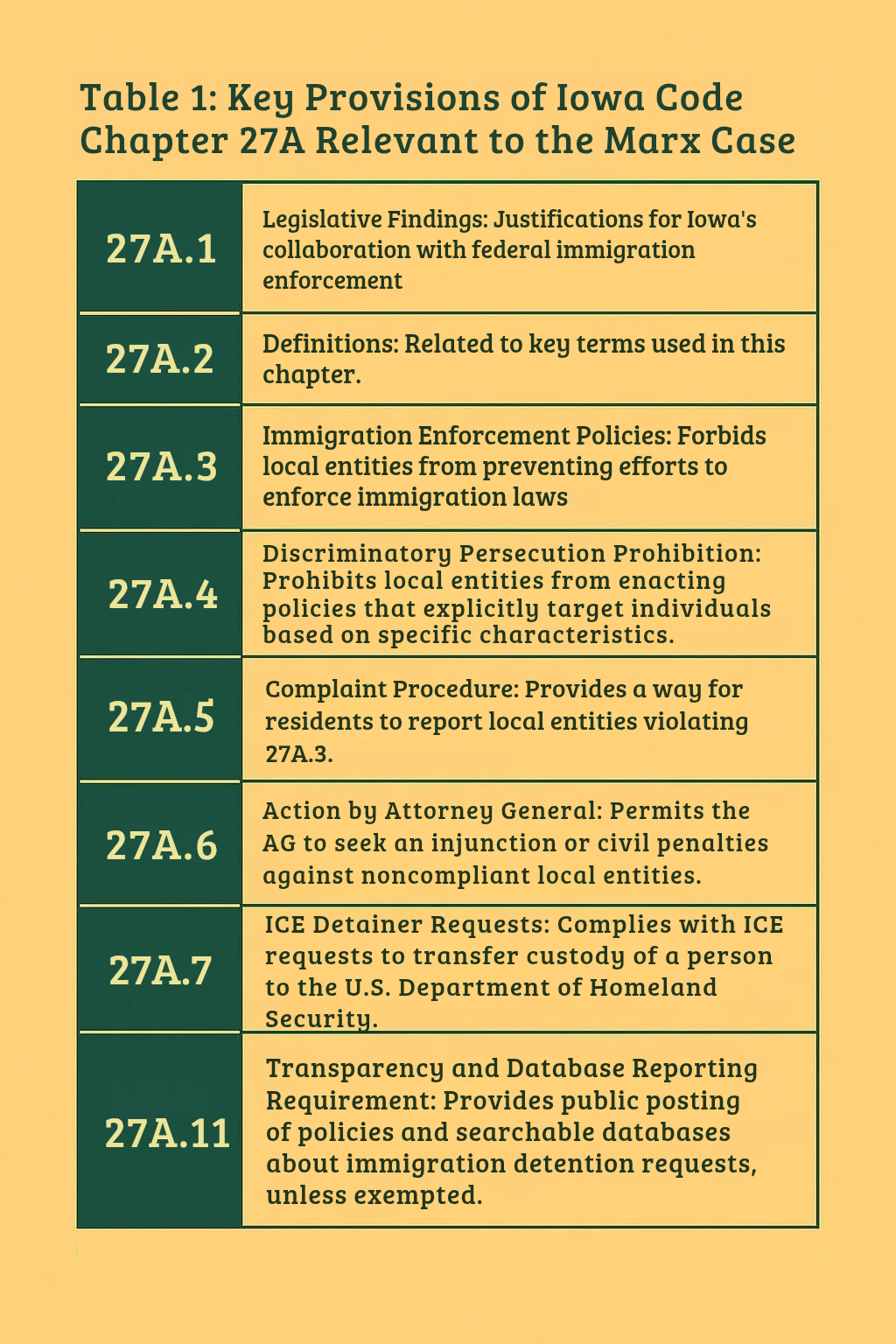

Iowa Code Chapter 27A, officially titled "ENFORCEMENT OF IMMIGRATION LAWS," was enacted in 2018 and is commonly referred to as Iowa's "sanctuary cities" law.1 Its main goal is to prevent local governmental entities from adopting policies or taking actions that hinder federal immigration enforcement within the state.2 The statute begins by defining key terms in Section 27A.1. A "local entity" is broadly defined to encompass the governing body of a city or county, including its officers or employees, such as a sheriff or police department.3 Its top aim is to prevent local entities from hindering federal immigration enforcement.

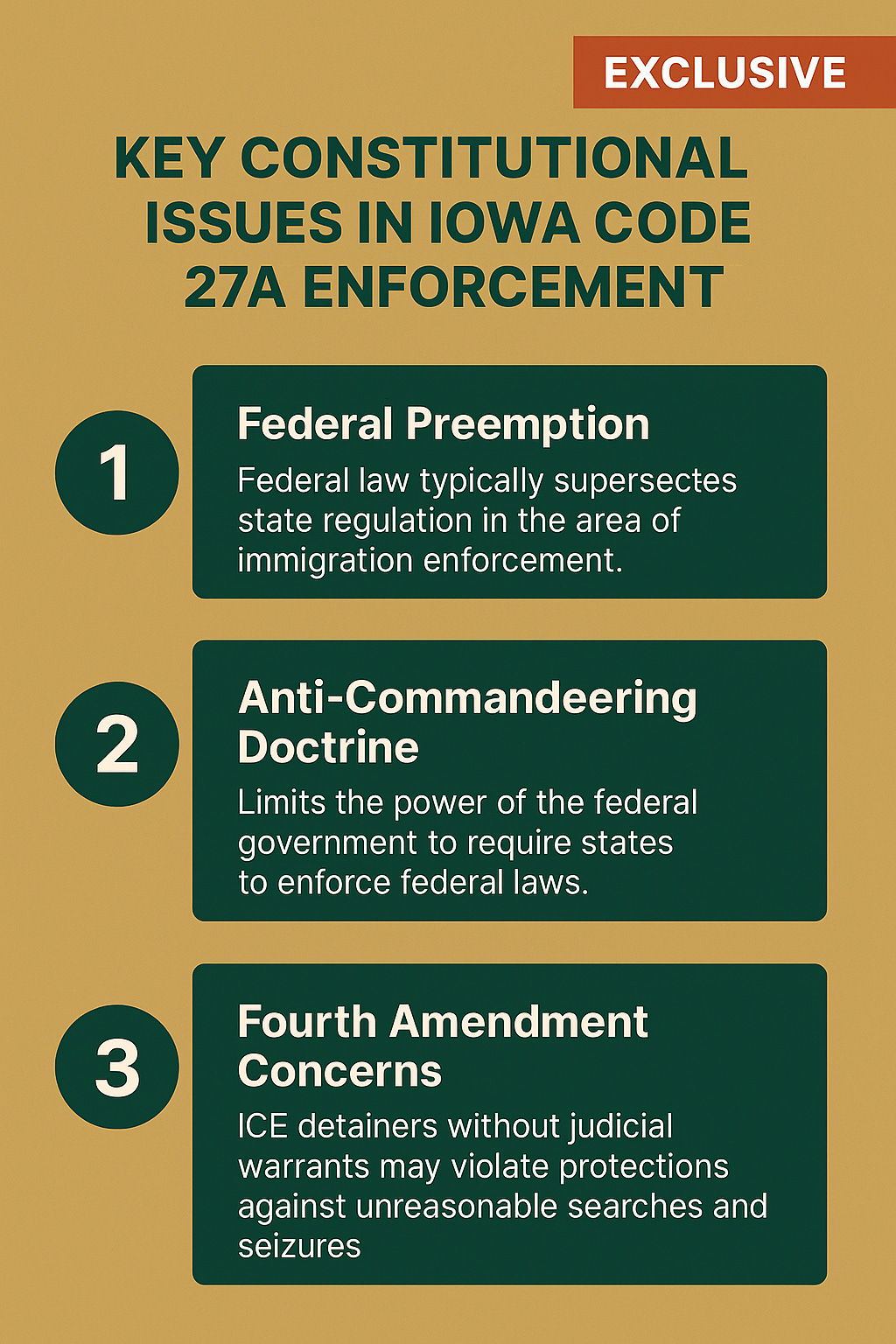

However, legal scholars and civil liberties advocates have raised significant constitutional questions regarding its provisions, citing potential concerns with federal preemption in immigration matters4, the anti-commandeering doctrine5—which prohibits forcing states to enforce federal law—and Fourth Amendment concerns related to honoring ICE detainers without judicial warrants.6 This upfront explanation clarifies the inherent legal shakiness of the statute being wielded. An "immigration detainer request" is specified as a written federal government request, typically from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), asking a local entity to maintain temporary custody of an individual.7

B. Core Mandates: Compliance and Prohibition

A core mandate of Chapter 27A is found in Section 27A.2, which stipulates that any law enforcement agency in Iowa having custody of a person subject to an immigration detainer request "shall fully comply" with the instructions contained within that request and any other legal document provided by a federal agency.8

Section 27A.4 is particularly central to the action against Sheriff Marx. It explicitly prohibits a "local entity" from adopting or enforcing any policy or taking "any other action" that "prohibits or discourages the enforcement of immigration laws."9 This prohibition extends to preventing or discouraging officers from inquiring about immigration status, sharing information with ICE, or assisting federal immigration officers.10

C. The Enforcement Mechanism: Complaints and Civil Actions

The enforcement mechanism is detailed in Section 27A.8. It allows "any person," including a federal agency, to file a complaint with the Attorney General, provided they offer supporting evidence.11 For a complaint to be valid, the Attorney General must determine that the alleged violation was "intentional".12 If deemed valid, the Attorney General must notify the local entity within ten days, informing them of the complaint and the grounds, and stating that a civil action may be filed if compliance is not achieved within 40 days. Should the local entity fail to comply within this period, the Attorney General must file a civil action in district court to enjoin the ongoing violation.13

D. Severe Consequences: Denial of State Funds

The most severe consequence of non-compliance is outlined in Section 27A.9, which mandates the denial of state funds. This provision states that "a local entity... shall be ineligible to receive any state funds if the local entity intentionally violates this chapter."14

This denial of funds applies to all state agencies for the state fiscal year following a final judicial determination that an intentional violation occurred.15 This statutory framework, particularly sections 27A.8 and 27A.9, establishes a direct and potent link between a complaint filed with the Attorney General and the potential for a local entity to lose all state funding. This creates a powerful, almost coercive, mechanism for state control over local immigration enforcement policies. The process begins with a complaint, which, if validated by the Attorney General as an "intentional" violation, leads to a notification and a limited window for the local entity to correct the issue. If the violation persists, the Attorney General must file a civil action. A final judicial determination of an intentional violation then triggers the mandatory denial of all state funds, a severe and non-discretionary penalty. This step-by-step process highlights how a complaint, once validated by the Attorney General and confirmed by a court, leads directly to severe financial penalties for the local entity. This structure empowers the state's top legal office with significant leverage, potentially compelling local governments to conform to the state's interpretation of the law under threat of financial ruin.

E. Path to Reinstatement

While severe, the law does provide a path for reinstatement of funds under Section 27A.10. Eligibility can be restored no earlier than 90 days after a final judicial determination if the local entity petitions the court and obtains a declaratory judgment confirming full compliance.16

F. The Overlooked Mandate: The AG’s Database

Finally, Section 27A.11 contains a critical, yet often overlooked, mandate: the Attorney General is required to "develop and maintain a searchable database listing each local entity for which a final judicial determination described in section 27A.9... has been made." This database "shall be posted on the attorney general's internet site."17

III. The Case Against Sheriff Marx: Free Speech, Detainers, and the AG's Legal Stance

A. Sheriff Marx's Facebook Post: The Catalyst

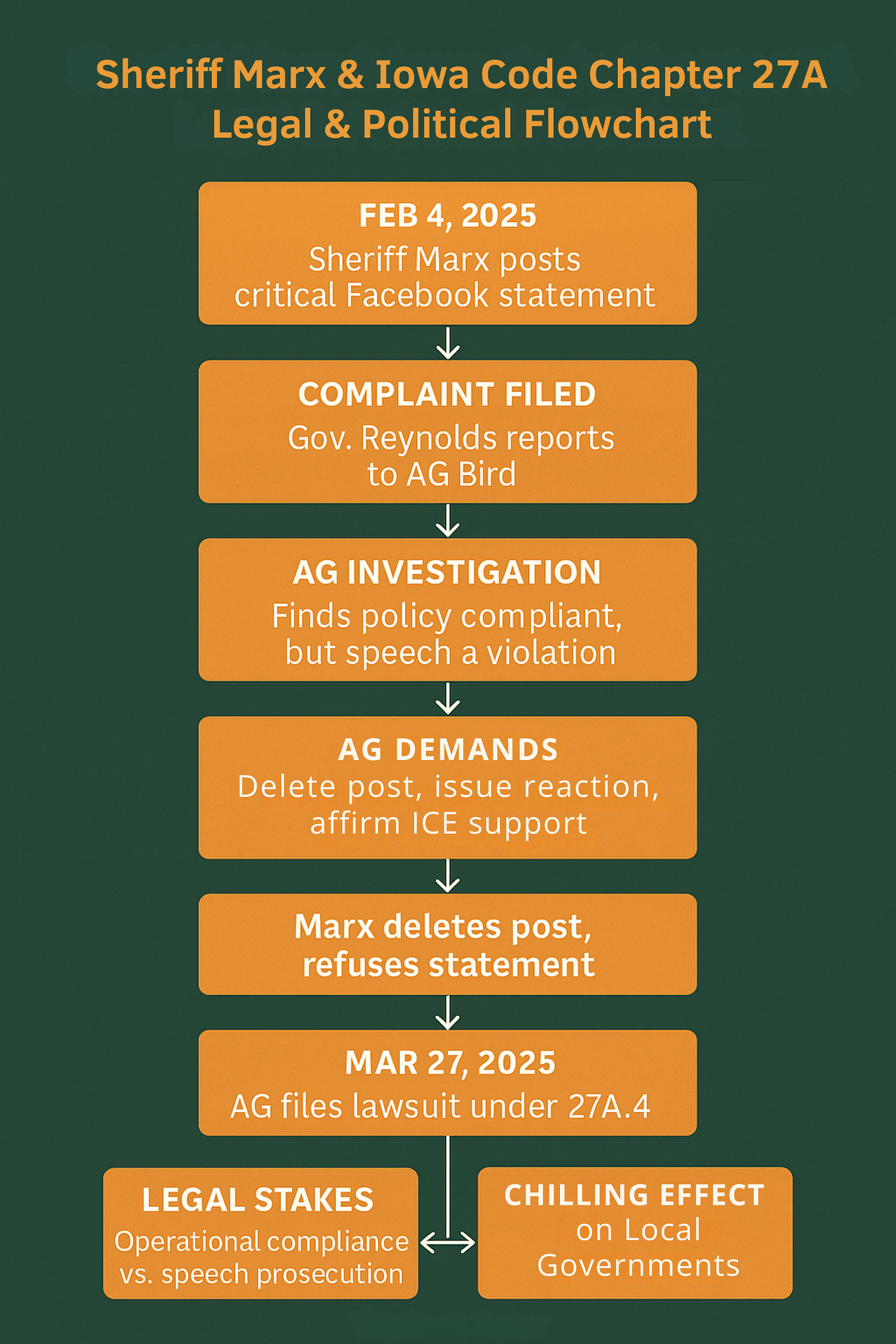

The immediate catalyst for the Attorney General's action was Sheriff Dan Marx's Facebook post on February 4, 2025.18 In this post, Sheriff Marx articulated his stance on immigration detainers, asserting that they were "violations of our 4th Amendment protection against warrantless search, seizure and arrest" and that his office had a "long-time stance on not recognizing detainers."19 He further stated his intention to "block, interfere and interrupt" ICE actions not supported by judicial warrants.20 Following this post, Governor Kim Reynolds filed a formal complaint with the Attorney General's office under Iowa Code section 27A.8, alleging that Sheriff Marx's statements constituted a violation of Chapter 27A.21

B. The AG's Investigation: Operational Compliance Confirmed

A critical finding from the Attorney General's own investigation was that the Winneshiek County Sheriff's Office policy was, in fact, compliant with Iowa Code Chapter 27A. This policy explicitly required employees to comply with ICE detainers and granted ICE officers access to the jail.22 Moreover, the investigation confirmed that the Sheriff's office had diligently honored all 21 ICE detainer requests received since November 26, 2018.23

C. The AG's Demand: Targeting Speech, Not Action

Despite this demonstrated operational compliance, the Attorney General concluded that making the Facebook post itself constituted an "intentional" violation of Iowa Code section 27A24 because it "discouraged" the enforcement of immigration laws.25 To remedy this alleged violation, the Attorney General demanded specific actions: the deletion of the offending post, an explicit retraction of support for it, and the posting of a new, prescribed statement affirming compliance with state and federal law, including ICE detainers.26

D. First Amendment Concerns: Public Employee Speech

The Attorney General's decision to pursue legal action against Sheriff Marx based on his social media statements (speech) rather than his official actions (which were found to be compliant with ICE detainer requests) represents a significant legal strategy that pushes the boundaries of Iowa Code Chapter 27A. This approach immediately raises substantial First Amendment concerns regarding public employee speech. The Attorney General's report explicitly acknowledges that the Winneshiek County Sheriff's Office policy is compliant with 27A and that the office has a verified record of honoring all ICE detainer requests received since 2018.27

This indicates that the Sheriff's Department was fulfilling the action-oriented mandates of the law. However, the Attorney General's complaint and subsequent lawsuit hinge solely on the interpretation that the Sheriff's Facebook post "discouraged" enforcement, falling under the "take any other action under which the local entity... discourages" clause of 27A.4.28 This expands the scope of "action" to include expressive conduct. This interpretation directly implicates the First Amendment rights of public employees.29

The Pickering Balancing Test and Garcetti v. Ceballos are the primary legal frameworks for evaluating such speech.30 Garcetti notably limits protection for speech made "under an employee's official duties," while Pickering protects private citizen speech on matters of public concern unless it unduly disrupts workplace efficiency.31

By focusing on the "discouraging" aspect of speech, the Attorney General avoids a direct challenge of the Sheriff's actual compliance with detainer requests, where her own investigation found no fault. Instead, she forces a legal battle over the scope of a public official's expressive rights, potentially aiming to establish a broad precedent that limits critical commentary or dissent, even when official duties are being performed compliantly.

This strategic choice to prosecute based on speech, despite compliant actions, suggests a deliberate attempt to expand the reach of 27A beyond operational non-compliance, effectively transforming a potential administrative compliance issue into a high-stakes free speech battleground, with significant implications for the expressive rights of public officials.

E. Legal Distinction: Detainers vs. Judicial Warrants

It is important to clarify the legal distinction between immigration detainers and judicial warrants, which was a point of contention in Sheriff Marx's original post. Immigration detainers are characterized as requests from ICE officials to hold individuals for up to 48 hours beyond their usual release time, based on probable cause but issued by an ICE officer, not a judge.32 In contrast, a judicially valid warrant is issued by a judge or magistrate after a determination of probable cause.33 While compliance with detainers is generally voluntary for law enforcement agencies across the U.S.34, Iowa's Chapter 27A uniquely makes compliance with these requests mandatory for local law enforcement within the state.35

F. Sheriff Marx's Refusal and the Lawsuit

Sheriff Marx complied with the demand to delete his original Facebook post but steadfastly refused to issue the specific remedial statement drafted by the Attorney General, deeming its language "not acceptable to the county."36 As a direct consequence of this refusal, Attorney General Bird filed a lawsuit against Winneshiek County Sheriff Dan Marx on March 27, 2025, in Polk County District Court, alleging a violation of Iowa Code Chapter 27A.37

The Attorney General's aggressive prosecution of Sheriff Marx for his social media comments, despite his office's demonstrated compliance with ICE detainer requests, creates a significant chilling effect on the free speech and independent thought of other public officials across Iowa.

The Attorney General, the state's chief legal officer, is using a powerful state law (27A) with severe potential penalties (loss of state funds) to target a publicly elected local official.38 This action is highly visible and sends a clear message.

Indeed, other rural Iowa sheriffs are reported to be "hesitant to speak on the record for fear of similar retribution," directly confirming that the Attorney General's action against Marx is already perceived as a warning or threat by other officials. If elected officials fear legal action and potential financial penalties for their counties simply for expressing critical views on state policy, federal actions, or constitutional interpretations, it will inevitably lead to self-censorship.

This stifles open and robust debate, which is fundamental to democratic governance and the ability of local leaders to represent their constituents' interests. The action also undermines the traditional autonomy of local elected officials to voice concerns or interpretations that may diverge from the state's executive branch, pressuring them into ideological conformity rather than allowing for independent thought and expression. The Attorney General's approach, by targeting speech rather than action, weaponizes the law to control the narrative and suppress dissent.

This not only impacts Sheriff Marx but sends a broader message that independent public discourse from local officials could come at a severe cost, ultimately weakening the democratic checks and balances inherent in a system of local control.

IV. The Phantom Database: A Deepening Crisis of Transparency and Accountability

A. The Mandated Database: A Cornerstone of Transparency

Iowa Code Section 27A.11 couldn’t be clearer. It mandates that the Attorney General “develop and maintain a searchable database listing each local entity for which a final judicial determination described in section 27A.9... has been made,” and that this database “shall be posted on the attorney general's internet site.” This provision wasn’t an afterthought—it was designed to guarantee transparency and allow Iowans to track how and where the state's immigration enforcement law is being applied.39

But as of late May 2025, no such database exists.

This absence isn’t speculative; It’s documented.

B. The Investigation: A Pattern of Evasion

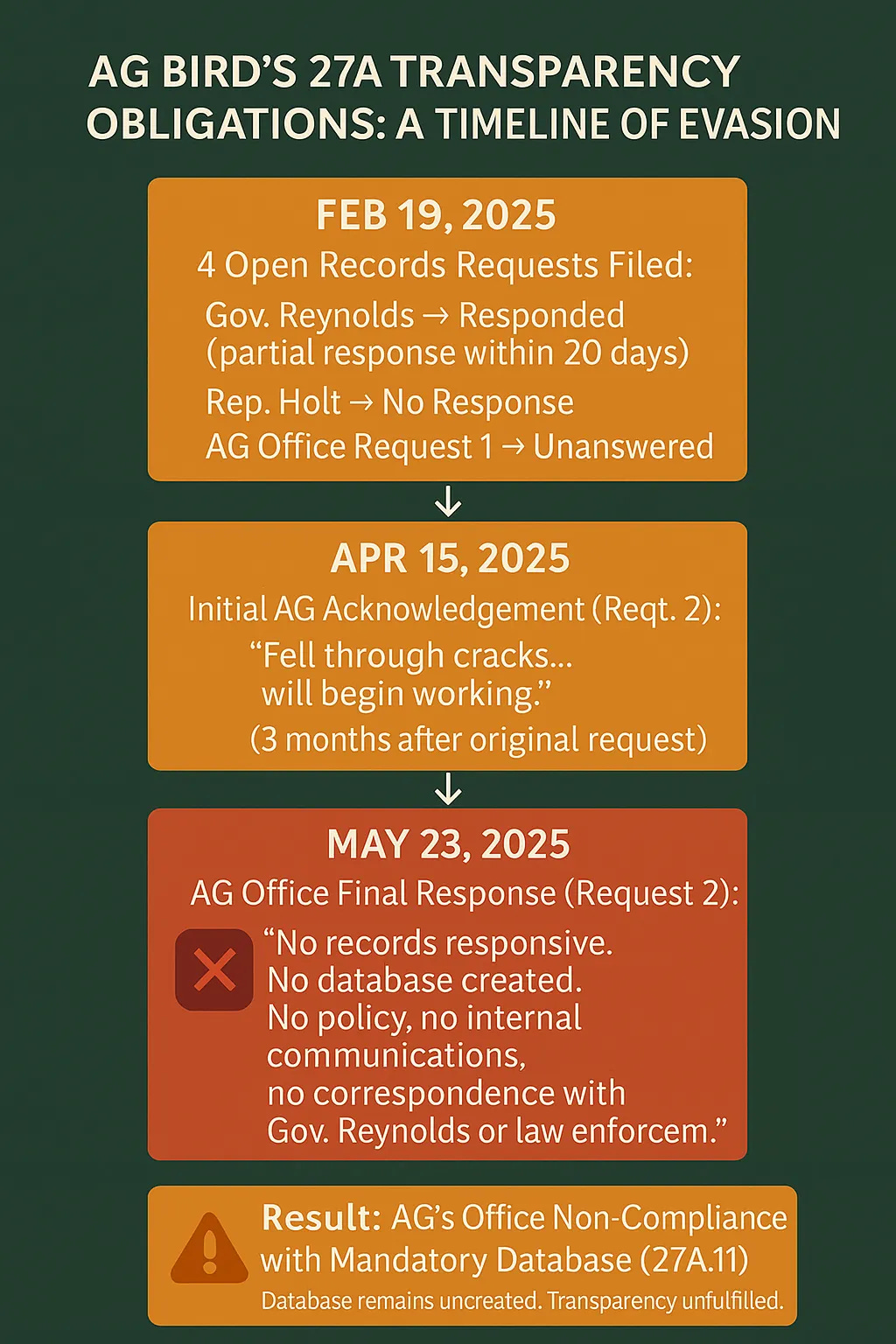

My investigation into this potential lack of transparency began with a series of Open Records Requests on February 19, 2025. I sent four requests: one to State Representative Steven Holt (which went unanswered, though House members often assert they are not required to respond), one to Governor Kim Reynolds's office asking for all communications related to Chapter 27A, and two separate requests to the Attorney General's office.

Here's how those requests unfolded:

February 19, 2025: Four Open Records Requests were submitted.

My initial request to the Attorney General's office, sent at 10:06:38 AM CST, specifically sought records related to the 27A.9 database, its creation, maintenance, policies, and any communications regarding compliance with law enforcement, the Governor's office, or the legislature. A second, broader request for all Chapter 27A communications was sent to the AG's office on the same day.

My request to Governor Kim Reynolds's office, also sent on February 19, 2025, at 5:13 PM, asked for all communications regarding the implementation or enforcement of Iowa Code Chapter 27A, internal memos, notes, and any reports or feedback on its impact.

AG Request 1 (Broad 27A Communications): This comprehensive inquiry for all communications related to Chapter 27A to this day, remains unanswered.

AG Request 2 (Targeted 27A.11 Database):

April 14, 2025: After more than 20 days with no response to my targeted database request, I sent a follow-up email noting the lack of acknowledgment and requesting a reply.

April 15, 2025: I received an initial acknowledgement reply from the "Open Records" email address, stating: "My sincere apologies, this somehow fell through the cracks on my end. This confirms receipt and I will begin working on your request." This initial reply was unsigned.

May 23, 2025: A full response was finally received. It was a generic, unsigned message from "Open Records" that read,

"Thank you for reaching out to the Iowa Attorney General's office, and a sincere thank you for your patience. After a thorough inquiry and search, we have no records responsive to your request. No database has been created because there have been no judicial determinations; therefore, there is also no policy/procedures regarding, no internal communications about its creation or maintenance, nor communications with law enforcement, the Governor's office, or the legislature about compliance reporting.”40

The Contradiction: This last part of the Attorney General's response is particularly striking. Just twenty days after my initial request, on March 6, 2025, at 10:37 AM CST, I did receive a response from Governor Reynolds's office to my broad inquiry for 27A communications. The Governor's office stated that they had directed their "technology office and/or staff... to search for all potentially responsive documents," and that "All records returned were reviewed". While the production was largely boilerplate, it was a response, including a data file that contained records. For the Attorney General's office to claim they have no records of communications with the Governor's office on this very law raises serious questions about the completeness of their search, or their willingness to disclose. The contrast is stark: the Governor's office, while providing mostly inconsequential records, at least acknowledged and produced something; the AG's office, despite being the chief enforcer of 27A and the entity mandated to create a public database, claims utter ignorance of any communications on the matter with the very offices they are interacting with.

This response isn't just inadequate—it's revelatory. It confirms the Attorney General's office has not created the database required by law, has no internal procedures for doing so, and has apparently never even discussed its legal obligation with the Governor's office or any law enforcement agencies. That's not bureaucratic oversight. That's institutional non-compliance by the state's top law enforcement official.

C. A Broader Pattern of Obstruction

This last part of the Attorney General's response is particularly striking. Just twenty days after my initial request, I did receive a response from Governor Reynolds's office to my broad inquiry for 27A communications. While largely boilerplate, it was a response, indicating that such communications do exist from the Governor's office regarding 27A. For the Attorney General's office to claim they have no records of communications with the Governor's office on this very law raises serious questions about the completeness of their search, or their willingness to disclose.

The contrast is stark: the Governor's office, while providing mostly inconsequential records, at least acknowledged and produced something; the AG's office, despite being the chief enforcer of 27A and the entity mandated to create a public database, claims utter ignorance of any communications on the matter with the very offices they are interacting with.

It confirms the Attorney General’s office has not created the database required by law, has no internal procedures for doing so, and has apparently never even discussed its legal obligation with the Governor’s office or any law enforcement agencies. That’s not bureaucratic oversight. That’s institutional non-compliance by the state’s top law enforcement official.

Worse, this lack of transparency mirrors a broader pattern of obstruction. According to an individual closely involved with the local response to the lawsuit and familiar with county residents' efforts, residents of Winneshiek County—more than twenty of them—submitted similar open records requests and were met with the same stonewalling tactics: excessive fee estimates, vague delays, and excuses about attorney redactions41. These are classic suppression techniques used to discourage public inquiry. But when the AG’s office itself is the subject of the law it’s failing to follow, these tactics become especially damning.

The contradiction is stark: Attorney General Bird is prosecuting Sheriff Marx under Chapter 27A while her office violates the transparency clause of the very same statute. She demands full compliance from others while admitting—flatly—that her office has done nothing to comply with 27A.11.

D. Policy Inconsistencies: Demands vs. Actions

The Attorney General's office has been involved in legal disputes over the withholding of public records. For instance, the Attorney General's office sued the Des Moines Register to prevent the newspaper from obtaining emails that Governor Reynolds claimed were protected by "executive privilege," a concept not explicitly an exemption in Iowa's open records law.42

Furthermore, in 2023, the Iowa Supreme Court rejected Governor Reynolds' attempt to dismiss a records-related lawsuit filed by liberal-leaning media outlets and the Iowa Freedom of Information Council, which accused her office of violating the state's open records law by ignoring requests and failing to produce records promptly.43 This indicates a systemic resistance to open government principles emanating from the state's executive branch, including the Attorney General's office.

The Attorney General's aggressive enforcement of Iowa Code Chapter 27A against a local sheriff—while simultaneously failing to comply with the Chapter's own explicit transparency mandate (27A.11) and demonstrating a broader pattern of obstructing public records requests—reveals a profound hypocrisy and a deliberate strategy to control information and evade public scrutiny.

Iowa Code 27A.11 unequivocally imposes a mandatory duty on the Attorney General to "develop and maintain a searchable database" of 27A violations and "post the database on the attorney general's internet site."44 This is a non-discretionary statutory obligation. The observed absence of this database from the Attorney General's official public website constitutes a direct violation of state law by the state's chief law enforcement officer.45

Concurrently, the Attorney General's office is actively and publicly pursuing legal action against Sheriff Marx under Chapter 27A, emphasizing the importance of compliance with the law.46 This creates a stark contrast between the Attorney General's demands of others and her own actions.

Indeed, this specific non-compliance is not isolated. The Attorney General's office has actively engaged in litigation to prevent the disclosure of public records47, and has been accused of bureaucratic delays and silence in response to Open Records Requests. This consistent pattern strongly suggests that the absence of the 27A.11 database is not merely an oversight but a deliberate choice.

Operating without this mandated transparency allows the Attorney General's office to control the narrative around 27A's application, potentially obscuring the full scope of its enforcement, the types of cases pursued, or the outcomes. This lack of transparency prevents public oversight and makes it difficult for journalists and other local entities to assess the fairness and consistency of the law's application.

The Attorney General's actions demonstrate a clear double standard: demanding strict adherence to one part of the law from local entities while apparently disregarding her own statutory obligations for transparency under another part of the very same law. This undermines public trust, raises serious questions about the thoroughness and fairness of the enforcement process, and contributes to a broader erosion of open government in Iowa.

V. The Political Undercurrents: Ambition, Retribution, and Power Consolidation

A. AG Bird's Gubernatorial Ambitions

Attorney General Brenna Bird, who made history as the first Republican Attorney General elected in Iowa since 197948 in November 2022, has openly signaled her intentions to run for Governor.49 Bird herself has acknowledged that running for governor is "not a light decision to make" and has expressed anticipation for sharing her plans for 2026.50

This high-stakes political environment is further solidified by recent developments in the Attorney General's race itself. Democrat Nate Willems has announced his campaign for Iowa Attorney General, setting the stage for a competitive election cycle and potentially influencing the calculus of incumbent actions.51

B. Alignment with MAGA Agenda

The complaint against Sheriff Marx was formally initiated by Governor Kim Reynolds52, who is described as a "close political ally" of Attorney General Bird. This connection suggests a potentially coordinated or ideologically aligned effort. The Attorney General's aggressive stance against a "sanctuary sheriff"53 and her emphasis on enforcing Iowa's "sanctuary county" law (Chapter 27A) aligns perfectly with a strong MAGA political platform on immigration enforcement.

Attorney General Bird's own public statements, such as "Iowa law is clear: counties and cities must comply with Iowa Code Chapter 27A... Any reports of sanctuary counties or sheriffs will be investigated,"54 underscore her commitment to this issue, which could be a key differentiator in a gubernatorial primary or general election.

Her public actions, including launching a campaign website and posting social media videos featuring President Donald Trump praising her and thanking her for her support, clearly indicate a strong alignment with the MAGA political base.

C. Strategic Case Selection: Speech as a Political Tool

The decision to sue Sheriff Marx over his speech (a Facebook post) rather than his department's actions (which were found compliant) further suggests a focus on public messaging and setting a precedent that discourages dissent, serving a political purpose beyond strict legal compliance.

Attorney General Bird's confirmed gubernatorial ambitions for 2026 appear to serve as a significant political motivator for her aggressive and high-profile enforcement of Iowa Code Chapter 27A against Sheriff Marx.

This transforms a legal dispute into a strategic political maneuver aimed at bolstering her conservative credentials and demonstrating a tough stance on immigration and local control, thereby advancing her political career.

As a first-term Republican Attorney General55 with clear gubernatorial aspirations, actively campaigning and aligning herself with prominent conservative figures like Donald Trump56, the enforcement of "sanctuary county" laws (Chapter 27A) and a firm stance on immigration are key issues for the conservative base that Bird needs to energize for a successful gubernatorial bid.57

The strategic case selection, originating from Governor Reynolds, a political ally58, and focusing on the Sheriff's speech rather than operational violations, suggests a calculated move to create a high-profile case that resonates with her political platform. By taking a strong public stance against a "sanctuary sheriff," Attorney General Bird can project an image of a decisive, law-and-order leader committed to enforcing state mandates. This narrative can be leveraged for political gain, demonstrating her commitment to issues important to her potential voter base.

D. Chilling Effect on Local Officials

Beyond the immediate case, the Attorney General's aggressive enforcement creates a "chilling effect" on other local officials, discouraging dissent and promoting conformity to the state's executive branch, effectively consolidating political power and ensuring ideological alignment across local governance, which benefits a potential gubernatorial administration. The timing, nature, and target of this lawsuit are not merely coincidental; they are deeply intertwined with Attorney General Bird's political ambitions, suggesting that the legal action is a strategic component of her broader political campaign, designed to enhance her profile and demonstrate her commitment to a particular ideological agenda ahead of the 2026 gubernatorial race.

E. Fracture within Law Enforcement

This political undercurrent has created palpable tension within the state's law enforcement community. Reports indicate that other rural Iowa sheriffs are either "publicly expressing solidarity or quietly signaling concern" over the Attorney General's actions. Crucially, many are "hesitant to speak on the record for fear of similar retribution," indicating a real and perceived threat to their professional autonomy and potentially their careers. Internal discussions within law enforcement associations are said to be "heated," pointing to a "potential fracture" within the community. Elected community officials are hesitant to speak about immigration. Where is the line drawn?

Legal observers have noted this raises critical questions about the Attorney General's underlying intent: Is this an attempt to set a broad precedent for compliance, or to silence dissenting voices within local governance and ensure ideological alignment?

VI. The Unseen Costs: Financial Burden on Localities and Weaponization of Law

A. "Astronomically Expensive" Legal Defense

Beyond the legal and transparency issues, an under-reported angle is the potential financial burden this unchecked use of 27A could place on local communities. Defending against a state-level civil action, even if the local entity ultimately prevails, can be "astronomically expensive." This financial strain would directly fall upon the taxpayers of Winneshiek County if Sheriff Marx is forced to defend himself and his office.

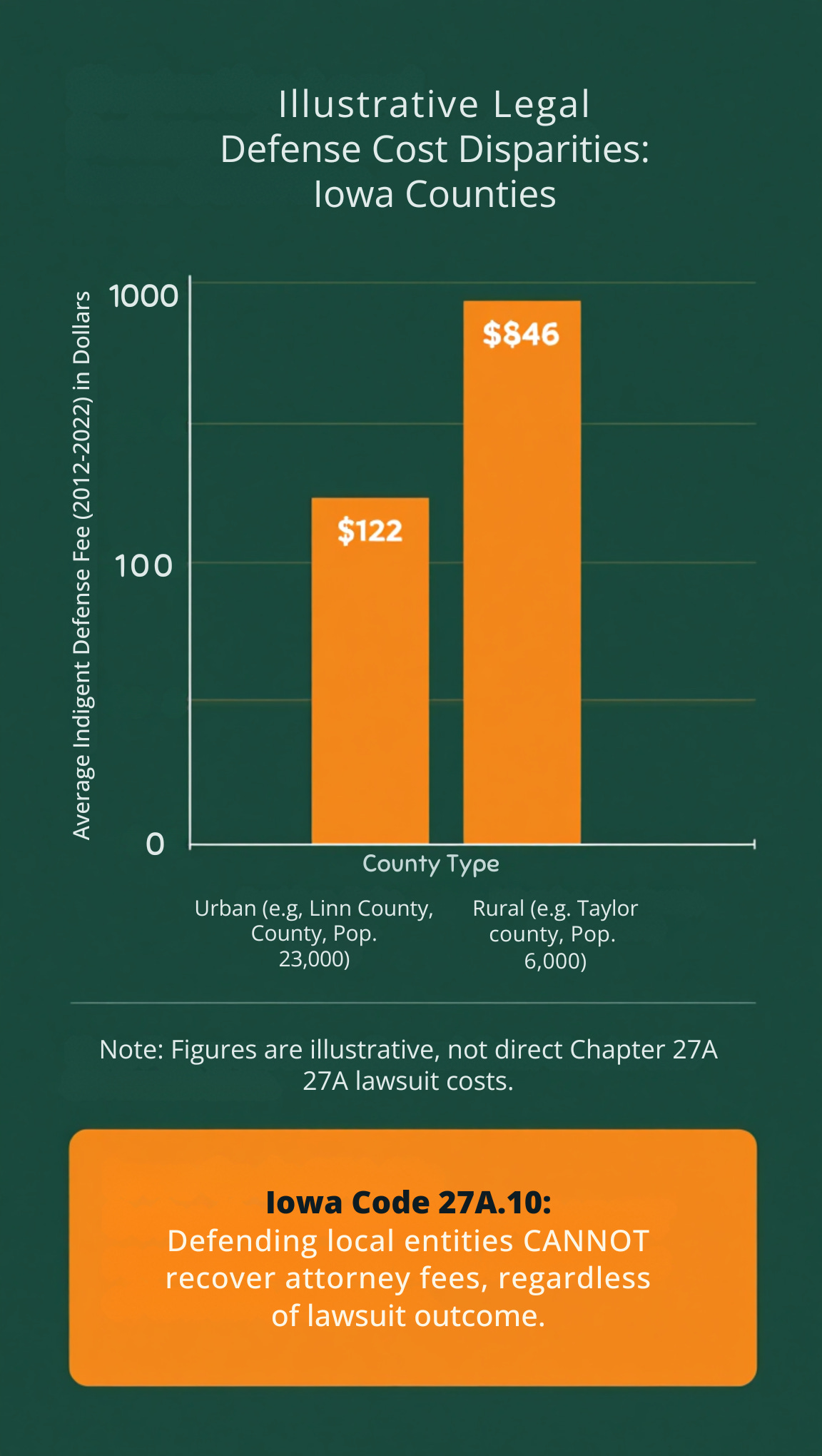

A critical, often overlooked, aspect of Iowa Code Chapter 27A is Section 27A.10, which explicitly states that "A party shall not be entitled to recover any attorney fees in a civil action described by subsection 1."59 This means that even if Winneshiek County successfully defends itself against the Attorney General's lawsuit, it cannot recoup its legal expenses from the state, ensuring a significant financial loss regardless of the judicial outcome.

While direct data on the costs of defending Iowa counties against state lawsuits under Chapter 27A is not readily available, broader information on legal defense costs within Iowa provides valuable context. Iowa is noted for imposing some of the highest fees in the nation for legal aid, even charging indigent individuals for public defenders if they are acquitted or charges are dropped.60 The hourly rate for court-appointed attorneys in Iowa is notably low at $76/hour, a rate that "barely covers overhead costs" for most law offices.61 This suggests that securing high-quality private legal counsel for a complex, high-stakes state-level civil litigation would entail significantly higher costs, further burdening local budgets.

B. Disparity in Legal Resources: Rural vs. Urban

Data indicates a disparity in legal costs across Iowa: rural counties, such as Winneshiek, often face higher average indigent defense fees (e.g., Taylor County at $846) compared to urban counties (e.g., Linn County at $122).62 This disparity highlights the disproportionate financial vulnerability of smaller, less-resourced jurisdictions. The state's recoupment rate for indigent defense fees is remarkably low (around 3% or less for the last decade), indicating that the financial burden largely falls on state appropriations or, by extension, on local entities when they are responsible for their own defense.63

C. The Mechanism of Financial Coercion

The legal and financial structure surrounding Iowa Code Chapter 27A, particularly the mandatory denial of state funds for intentional violations and the explicit prohibition on recovering attorney fees by the defending local entity, effectively allows the Attorney General's office to weaponize legal action as a means of financial coercion against local governments. This disproportionately impacts smaller, rural counties and can compel compliance through economic pressure rather than purely legal merit.

The most direct and severe consequence of a judicial finding of an intentional violation under 27A is the mandatory denial of all state funds to the county for the subsequent fiscal year.64 This is an extremely powerful and potentially crippling financial blow to any local government. Even if a local entity successfully defends itself against the Attorney General's lawsuit, Iowa Code 27A.10 explicitly states that "A party shall not be entitled to recover any attorney fees."65 This means that, regardless of the outcome, the county will incur substantial legal expenses that cannot be recouped from the state.

The state, represented by the Attorney General's office, possesses vast legal resources and a budget supported by statewide taxation. In contrast, local entities, especially smaller, rural counties like Winneshiek, operate with comparatively limited budgets and often smaller, less specialized legal departments. This combination of a severe mandatory penalty and unrecoverable defense costs creates a powerful financial disincentive for local entities to challenge the Attorney General's interpretations or actions.

The sheer financial threat can pressure local governments into compliance, even if they believe they have a strong legal defense or that the Attorney General's action is politically motivated, simply to avoid the potentially "ruinous legal fees" or the loss of state funds. This financial pressure can effectively suppress local dissent, independent decision-making, and the willingness of local officials to voice concerns or criticisms that diverge from the state's narrative. It compels local governments to align with state directives to avoid economic hardship, thereby undermining the principle of local control. The legal framework of 27A, particularly its financial penalties and the non-recovery of legal fees, transforms legal enforcement into a potent tool for financial coercion. This allows the state to exert undue influence over local governance, potentially forcing conformity and stifling opposition through economic means rather than purely legal arguments.

D. Anti-SLAPP Laws: A Relevant Parallel

This raises "critical questions about fiscal responsibility and the potential for the AG's office to weaponize legal costs to suppress local dissent." If Chapter 27A becomes a favored tool for the Attorney General, how many other smaller counties or municipalities could face ruinous legal fees defending against politically motivated charges, especially if they lack the resources to fight back effectively? It is noteworthy that Iowa has enacted anti-SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) laws, designed to prevent lawsuits intended to "silence critics or intimidate those who exercise their free speech rights" by burdening them with the cost of defense.66 While the Marx case is not explicitly a SLAPP suit, the underlying concern about using legal action to financially exhaust and silence opponents is highly relevant to the implications of the Attorney General's actions.

VII. Broader Implications: Undermining Local Control and Democratic Norms

A. Beyond One Case: Abuse of Power and Trust

This isn't just about one Sheriff or one county. It's about whether the state's top legal officer believes they are above the laws they are sworn to enforce. It's about whether Iowans can trust that new, powerful, and "untested" statutes will be applied fairly and transparently, or if they will become tools for political maneuvering, shielded from public scrutiny. This situation powerfully echoes broader patterns of power consolidation and disregard for democratic norms detailed in "The Cross and the Capitol." It suggests that the "Church-to-Statehouse Pipeline" isn't just about specific ideological bills; it's about fostering an environment where accountability withers and power operates unchecked, specifically targeting voices that challenge the dominant narrative.

B. Erosion of Local Control

The action against Sheriff Marx, spurred by political complaints and prosecuted under a legally dubious and selectively transparent statute, serves as a stark warning. It represents a worrying trend of state overreach, chipping away at the long-held principle of local control—a cornerstone of Iowa's governance. When a state Attorney General can seemingly weaponize an obscure law and then refuse to comply with its own transparency mandates, the very foundation of democratic checks and balances is undermined.

C. Free Speech Under Threat: Public Employees and Social Media

The case against Sheriff Marx directly implicates the First Amendment rights of public employees, especially concerning their use of social media.18 The legal precedents governing public employee speech are primarily the Pickering Balancing Test and Garcetti v. Ceballos.67 The Pickering test requires a balance between the employee's interest as a citizen in commenting on matters of public concern and the government employer's interest in promoting workplace efficiency and avoiding disruptions.

Speech on matters of public importance, such as government policy or constitutional interpretations, lies at the core of First Amendment protection.68 The Garcetti ruling, however, limits this protection, stating that speech made "pursuant to an employee's official duties is not protected by the First Amendment."69

A central legal question in Sheriff Marx's case will be whether his Facebook post constitutes "private citizen" speech (protected under Pickering) or "official duty" speech (potentially unprotected under Garcetti). The Attorney General's aggressive pursuit of this case, focusing on the Sheriff's expression rather than his department's operational compliance, sets a troubling precedent for the free speech rights of elected officials and public servants who might wish to voice dissent or criticism of state policy.

VIII. Conclusion

The ongoing legal battle between Iowa Attorney General Brenna Bird and Winneshiek County Sheriff Dan Marx transcends a mere local dispute; it illuminates critical vulnerabilities within Iowa's governance structure, particularly concerning transparency, local autonomy, and the exercise of free speech by public officials. The Attorney General's office is aggressively enforcing Iowa Code Chapter 27A, a law designed to mandate local cooperation with federal immigration efforts, by targeting a sheriff whose department was found to be operationally compliant with ICE detainer requests. The prosecution hinges on the sheriff's social media statements, an interpretation that broadens the law's reach into the realm of expressive conduct and raises significant First Amendment concerns.

This selective enforcement is compounded by the Attorney General's apparent non-compliance with Section 27A.11, which mandates the creation of a public database of Chapter 27A violations. The absence of this database, coupled with a pattern of stonewalling public records requests, suggests a deliberate strategy to control information and evade public scrutiny. This double standard undermines the very principles of open government that the Attorney General is sworn to uphold.

Furthermore, the context of Attorney General Bird's gubernatorial ambitions for 2026 suggests a political dimension to this legal action. The high-profile pursuit of a "sanctuary sheriff" aligns with a conservative political platform, potentially serving to bolster her credentials and demonstrate a tough stance on immigration and local control. This strategic use of legal authority for political gain creates a chilling effect, discouraging other local officials from expressing independent views for fear of similar retribution and fostering a climate of ideological conformity.

Finally, the financial implications for local communities are stark. The mandatory denial of state funds for intentional violations under Chapter 27A, combined with the explicit prohibition on recovering attorney fees, creates a powerful mechanism for financial coercion. This disproportionately burdens smaller, rural counties, compelling them to conform to state directives through economic pressure rather than purely legal merit.

The people of Winneshiek County, and indeed all Iowans, deserve answers. They deserve an Attorney General who upholds all laws, not just those convenient for a political agenda. They deserve transparency, not stonewalls. The fight for accountability in Iowa continues. And the silence from the Attorney General's office on Iowa Code Chapter 27A is becoming deafening—a silence that speaks volumes about the state of democracy's promise in Iowa.

Disclosure: This article is based on public records, statutory review, publicly reported information, and open records requests submitted by the author. All characterizations are presented as analysis of matters of public concern involving public officials, and are protected opinion under applicable First Amendment and fair reporting standards. All artwork is AI generated and prompt engineered by the author.

Works Cited

CHAPTER 27A, Author's note: The interpretation that Iowa Code § 27A.11 imposes a current, mandatory duty on the Attorney General to “develop” the specified database—distinct from the contingent act of “listing” entities—is grounded in established principles of Iowa statutory construction. Iowa Code § 4.1(30)(a) dictates that “shall” imposes a duty. Furthermore, the presumption that “the entire statute is intended to be effective” (Iowa Code § 4.4(2)) requires giving independent meaning to “develop,” separate from “maintain” or “list”. This ensures the transparency objective of § 27A.11 is not indefinitely deferred by the absence of entities to list, as the system itself must first be created to enable timely public access when a judicial determination occurs.

State of Iowa v. Dan Marx, Petition, Iowa District Court for Polk County, filed March 27, 2025. File on record with author.

State of Iowa v. Dan Marx, Petition, Iowa District Court for Polk County, filed March 27, 2025. File on record with author.

CHAPTER 27A, Authors Note: The interpretation that Iowa Code § 27A.11 imposes a current, mandatory duty on the Attorney General to “develop” the specified database—distinct from the contingent act of “listing” entities—is grounded in established principles of Iowa statutory construction. Iowa Code § 4.1(30)(a) dictates that “shall” imposes a duty. Furthermore, the presumption that “the entire statute is intended to be effective” (Iowa Code § 4.4(2)) requires giving independent meaning to “develop,” separate from “maintain” or “list”. This ensures the transparency objective of § 27A.11 is not indefinitely deferred by the absence of entities to list, as the system itself must first be created to enable timely public access when a judicial determination occurs.

Timothy Tucker, Email correspondence with Iowa Attorney General's Office (openrecords@ag.iowa.gov), "RE: Records Request for Iowa Code Chapter 27A Correspondence and Data," received May 23, 2025.

Anonymous Source

Iowa AG Brenna Bird Teases 2026 Bid For Governor YouTube KCAU-TV Sioux City